In addition to the main line-up of plays at ITFoK 2020, the festival also stages a program of performance poetry. What does poetry mean when it is being performed? Is performing poetry a reference to transgressive aesthetic or dissident political practice? I am delighted to invite M R Vishnu Prasad and Sudheesh Kottembram, who have co-curated an excellent program of performance poetry titled 'Kalathatt'. Kalathatt refers to a wooden leaf-thatched open platform, which served as resting stations for pedestrians and travellers in Kerala. The famous performance poet, Kunchan Nambiyar, is believed to have used these spaces as his stage for Tullal performances. The program 'Kalathatt' accentuates the memories of a performance tradition which has historically emerged as a composite form of theatre and poetry. Kalathatt features 16 eminent poets from all generations in Kerala. As part of International Theatre Festival of Kerala. Do come! January 20-29, 2020, at KSNA Thrissur.

ITFoK Curation 2020 - II

An allied event at the International Theatre Festival of Kerala is close to my heart. It is a program of 'Films-On-Theatre'. Theatre and Film are often kept divorced as mediums and identities, but their histories intertwine in more ways than one. An emerging interest in film-making has attempted to document performance practices by initiating a fresh dialogue between theatre and film, and in doing so, pushes the boundary of both mediums. In curating this, I wanted to address the desperate need to archive performance practices across India. Not only the forms of theatre which have become vulnerable amidst forces of urbanisation, and as a consequence are struggling to sustain themselves, but also theatres of modern India which were led by iconic artists, but ones that find themselves discontinued and lost posthumously. This program screens a selection of eight films for the festival audience, so we may access radical forms of theatre that are otherwise inaccessible, and also nurture our love for the theatre archive. Much gratitude to supporters, directors and producers for lending their films for screening at ITFoK 2020.

ITFoK Curation 2020 - I

The International Theatre Festival of Kerala opened with an excellent trio of plays, from Brazil, U.K. and India -

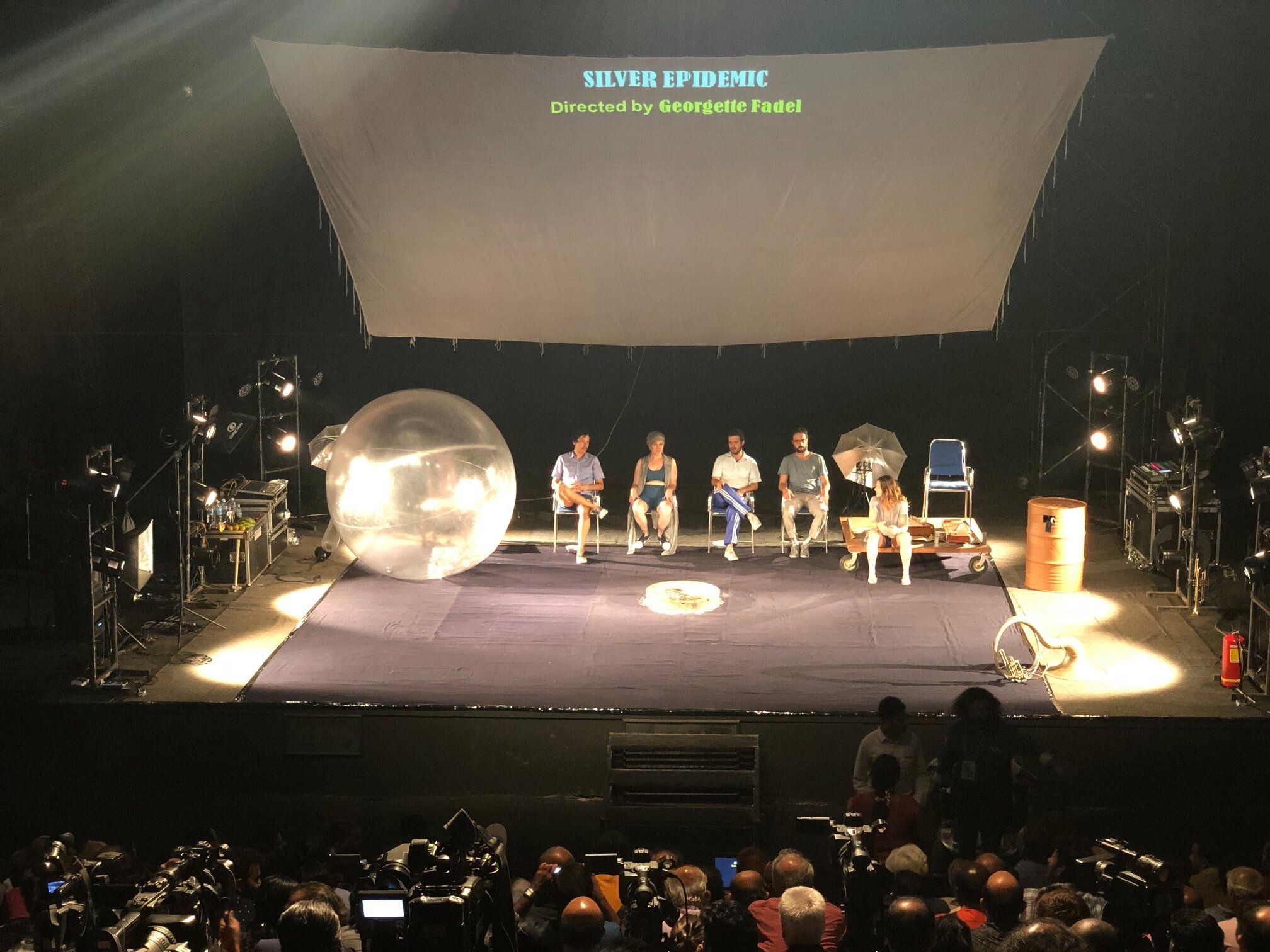

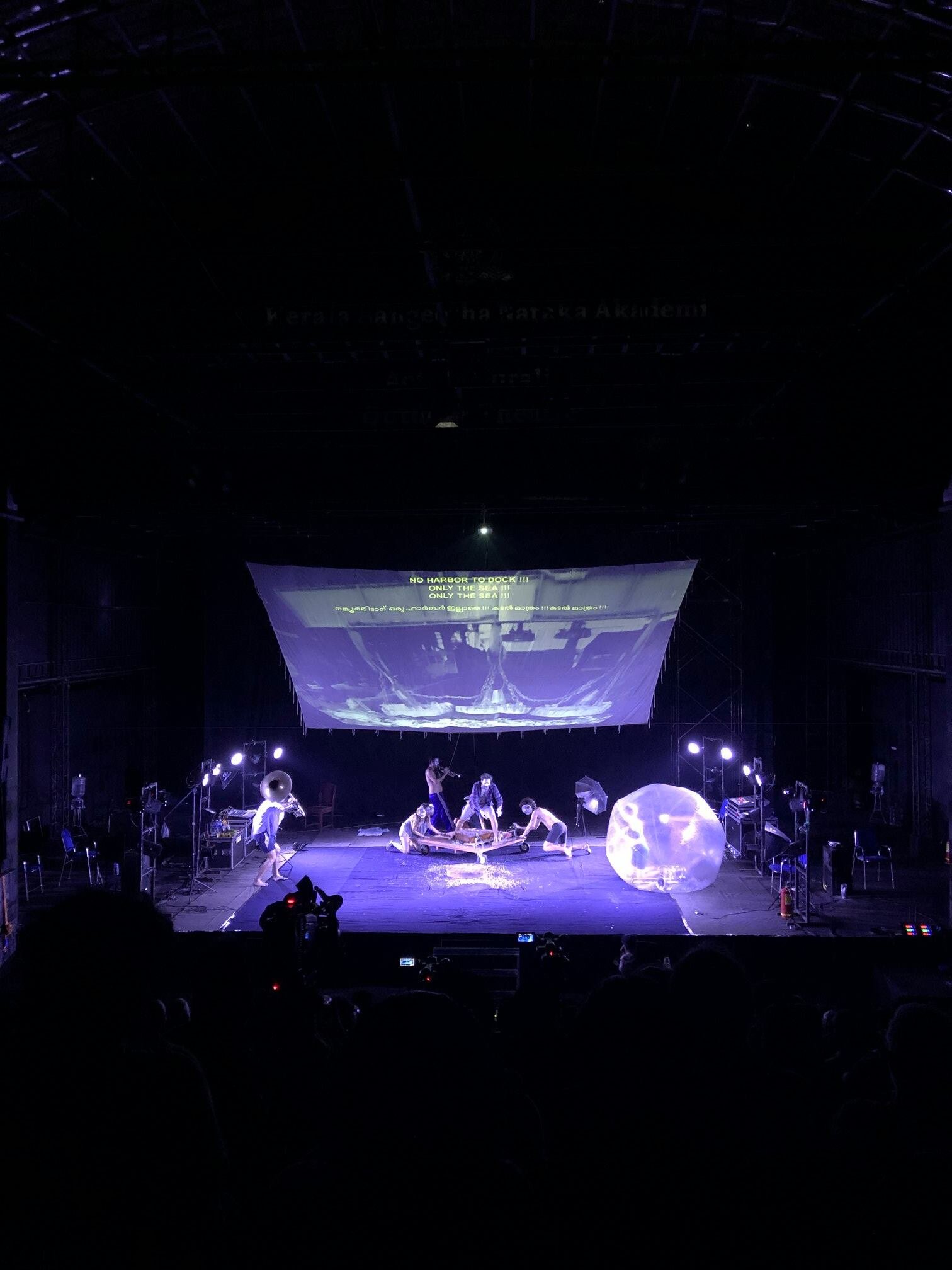

SILVER EPIDEMIC, the play from Brazil, entangled body, gesture, and coins in thousands, juxtaposing ‘honourable men' against the disenfranchised, the outcasts, the people of 'Crackland' who repeatedly get attacked by the police. Actors painted their bodies with silver in order to mask their fate, to inhabit a ‘silver universe’. They performed a disturbing doom - eating, drinking and shitting silver, broadcasting themselves, and yet remaining invisible. Verônica Lo Turco Gentilin

TOLD BY THE WIND was exactly that; a quiet performance that blended literature, movement and silence, evoking a series of metaphors with its fragmented yet beautiful Haiku-styled phrases. A bird, a dew drop, a step; with Zen-like poise, Phillip Zarrilli and Jo Shapland held the stage with their masterly bodies, and the fragility of their ageing. Personally, I haven't watched 70+ performers perform a poetry of life with the texture of vulnerability, sincerity, and poise as Phillip and Jo did.

EIDGAH KE JINNAT, a play that we must all watch in India today. Abhishek Majumdar the brilliant and bold playwright brought to stage the humanity amidst the crisis in Kashmir. The several intersecting narratives the play presents must be understood and articulated if we are to stand with the people and their region, the voices and their freedoms. Some memorable performances, especially by Ashwath Bhatt and Ajeet Singh Palawat

Complex Simplicity

My grandfather read and wrote in Urdu, and speaks Punjabi, Hindi, Urdu, and English in that order of ease. He maintained a private diary till very recently, in which he collected scraps of poetry, absurd news clippings, photos, handwritten letters, and leaves that fell on him during long winding walks. He remembers having grown up in a neighbourhood where identity and culture flowed effortlessly into one another. He identifies as Hindu by birth, Muslim by culture. Blasphemous, you declare. It is simple, he would say.

Partition tore through his neighbourhood, and forced them to flee Sialkot to come take refuge in Delhi. From a neighbourhood in which Hindus and Muslims were largely indistinguishable from each other, he found himself in a city erected along communal lines. I remember him confessing how odd he felt to have only Hindu neighbours for miles. In the absence of concrete, neighbours marked their domestic spaces with sticks, ropes and bricks, and looked after each other’s allotted properties. None had the wherewithal to begin building a house immediately, let alone a nation. They started by living in the open, inhabiting a blueprint drawn on soil, upon which got built a room, then another, and over years their house, their neighbourhood, and along came a nation. Unimaginable, you utter. It is simple, he would say.

He mastered History and became a high school teacher. He answered Gandhi’s call for building the nation by volunteering for community work - building and maintaining parks, organising medical camps, opening evening schools, offering tuition for free, mediating conflicts in the neighbourhood, dismissing offers to hold a post of authority offered in gratitude. He built neighbourhoods wherever he moved, crisscrossing the city from his young days in Karol Bagh, to his settled days on Vikas Marg, to his senior days in Gurgaon now. On one occasion, he ensured that a make-shift school got erected on unused land in his locality, land that was being encroached upon by temple construction in gross violation of public property. He achieved this with his neighbours without making a single enemy, or receiving any threat. Unthinkable, you exclaim. It is simple, he would say.

He lived by Gandhi’s idea of ‘serving the neighbour to serve the country’. At any rate, he has always struggled to grasp that which he could not circumambulate the edges of. He belongs to a nation called neighbourhood. Your neighbourhood is the only country you will ever really inhabit, he’d say.

Today, we see an unprecedented number of neighbourhoods pour out onto the streets in protest against divisive politics. Neighbours are looking out for each other, just like they did back then when the nation was being built. Neighbours are protecting each other just like they did back then when there were no houses. Neighbours are keeping safe the blueprint of this nation just like they did back then for their own houses. For this country is nothing more than a cluster of neighbourhoods built by countless people like this one grandfather, who, after having spent a lifetime building neighbourhoods, when asked today, if it is still possible to do it all over again, it is simple he would say.

Universe/ity

University and Universe have the same ring. Every country has at the very least a university, in where a universe flourishes. A university is where the real country is, or should be. In there you find adult life for the first time, the joy of separating the whims of a country from evidences, the delight of waking up to your peoples' genius and hypocrisy. University attendance is universally low in lectures, and characteristically high on campus. The open grounds, the tea shop, the hostel, the dramatics/debating/music clubs, the all-night cafe, college elections, is where the real university is, where you learn that what you do can count, has consequences, and that is contagious. You get university fever, and it infects your entire universe. This is the allure of a university, one that you never found at home, one that you will not find the moment you step out (some of us never do!). A university is where you put on headphones to shut out noise so you can listen more carefully, test how your own voice sounds, and gingerly attempt to utter original sounds if indeed fortune favours you. A university works if the entire universe is invited to inhabit it, and that must mean that it is universally funded by the public. Countries emerge out of universities, not the other way around. To see a country attacking its own university is to declare war upon its own universe. And if you do not have a universe of your own you must live in somebody else’s universe. And we all know what a shame that is! Stand with publicly funded universities, stand with #jnuprotest, stand with all students who fight for a better universe.

Phantom Sun

Faizabad District Judge KM Pandey made the decision to open the gates of the Babri, back in February of 1986, assuring everybody that heavens will not fall if the locks are removed. In his autobiography, he mentions that his decision was validated by a black monkey, who sat holding the flag post on the roof of the court all day long, and despite offerings of groundnuts and fruits from thousands of people of Faizabad and Ayodhya, refused to accept any. The judge spots the black monkey later in the verandah of his bungalow, and salutes him, taking him to be some divine power. Hon’ble Judge Pandey and Philip Lutgendorf remain separated by a phantom degree of freedom. Lutgendorf, an American Indologist known for his studies on the monkey-god, reminds us that the theological significance of Hanuman emerged about 1,000 years after the composition of the Ramayana, in step with the arrival of Islamic rule in the Indian subcontinent. By this time, stories and folk traditions had begun to reformulate Hanuman not only as a divine being, but an inspiration for martial artists and warriors, crafted to inspire the lazy, ambivalent devotee to toughen up, to turn monks into soldiers, to organise against threats violently, alien and imagined. A militant monkey cannot exist without devotion, and devotion must know no other monkey.

And so the earth turned and grounds swell and monkeys trained, till Gandhi, the master of symbology, picks up on this undercurrent in the 20th century, and sets out to de-militarise the monkeys, to turn their overzealousness, needlessly brute, mindless observance inwards, to compel them to be contemplative, to open their hearts out like Hanuman, to ritualise for them the proverbial principle from Japanese folklore, to ’see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil’, to turn them into the Sanzaru wise monkeys. They say that Gandhi had originally summoned four monkeys; to un-see, to un-hear, to un-speak, he needed one to un-think too. Three stayed, the fourth one fled. The one on the extreme right. The one in black. And since, the black monkey is said to have receded to the forrest of the dark. No one knows if he is still alive (how can he be!), but common people believe that his apparition appears unexpectedly when someone is killed, that his phantom is mysteriously spotted at sites of assassination. Somehow, for reasons unexplained, this ghost of a monkey has never been captured by cameras at the scene of crime despite being visible, and is remarkably missing from re-enactments, especially from those killing scenes of Gandhi and others who were executed after him.

To everybody’s surprise, reports are emerging that, not unlike the fateful day in 1986, the spectre of the black monkey was briefly seen again today, although nobody is certain. What is certain is that the spectre continues to have a disfigured jaw, following a Puranic legend that baby Hanuman mistook the sun for a fruit, attempted to heroically reach for it, but got wounded and disfigured his jaw. Evidence or not, some say we might have all turned into the very phantom ourselves today, all our jaws look disfigured somehow. We too have mistaken everybody’s sun as our fruit, and consumed it as ours and ours only.

<This post is written in response to the Ayodhya verdict pronounced by the Supreme Court in India today>

Teachers' Day

I have never had any regard for the teacher as sacred, none for the student as a devout. The relationship between a teacher and student eludes categorisation. This relationship is heavily pedagogical, instantly romantic, and in any case, best left vague. We are engaged in a pas de deux; the teacher displays poise and steadies the student, and the student performs slow, erratic, elegant variations. The teacher plays the committed lover - loyal in their presence, in their address, in their intention, in their concern. The student is at all costs promiscuous - running wild, experimenting, choosing from an array of options, indiscriminately, inconsistently. When the student utters a question, it is not to the teacher but of the world at large. When the teacher responds, it is never to the student, but for the future that is imminent. This forms the principle cultural model for free relationships between us, the old and the young. Our relationship has gallantry, respect, ardent love and adoration, bashfulness, reciprocal love, and wishful looks. And this is what I have shared with these two old folks. Humble as they are, today I name you for the devastatingly poetic impact you have had on my life. Happy teachers' day you pesky elders - Keval Arora, Anuradha Kapur

O Ganesh

An inescapable irony marks the sudden rise of Ganesh Chaturthi celebrations in towns and cities across India. In 1890’s Maharashtra, Bal Gangadhar Tilak had identified Ganesh as ‘God for Everyone’. In the aftermath of Hindu-Muslim riots, Tilak urged people of new India to bring this private adoration of Ganesh to the public fore. Perhaps the chimeric playfulness of Ganesh’s body is an excellent metaphor for India’s syncretic culture. The elephant head offers the human body two sensorial gifts - a geography of memory, and an uncanny ability to hear deep sounds (from the past even). Plus, who doesn’t have an appetite for ladoos. No other mythic figure is more (un)naturally disposed towards an inter-faith dialogue than Ganesh is. But today, Ganesh Chaturthi springs up across India’s moral landscape, across the new urban markets of ‘pop-religion’ (ones which had not even heard of the festival up until very recently), not in an effort to extend the dialogue, but to aggressively reclaim the mythic figure in step with the virulent majoritarian impulse. Beware - Ganesh is an excellent listener; if he can listen to Vyasa’s voice and write down the epic Mahabharata without ‘pause and hesitation’, it is almost certain that he is writing his next epic tragedy listening keenly to the voices of our times today. <detail from a Hussain painting>

A Biscuit for Egality

She was India's first immortal child. She was in every house, on every chai stall, in every shop. She attended school year after year without needing to grow up. She was up before dawn for the first morning cup with grandma, before anyone else woke up. She was found whole, neatly stacked, in our bags on way to school, and in happy odds and ends on the way back. She was there when we forgot to bring lunch, she was there during class and after. She was in every pocket, in every tiffin, in every jar. She was there when radio was switched on, the newspaper opened, when TV was beaming. She was there when the house was full, she was there when I was dreaming. She wasn't a variable, she was steel. Everything else was an exaggerated deal. Do you ever remember meeting anyone who refused her? She was not a biscuit, she was egality. Quora says she is Neeru Deshpandey from Nagpur, I don't believe it. Wiki declares 'Gunjan Gundaniya', I don't believe it. The earnest Mayank Shah at Parle Products takes the folklore and rips it: It's actually an illustration by an Everest creative from the 60s, he says it. I still don't believe it. Ofcourse I knew she wasn't real to begin with. All she was, was egality, and now we have lost it.

<in response to everything around, triggered by the news that top biscuit maker Parle may cut up to 10,000 jobs as economy slowdown bites>

Jury for ITFoK 2020

How do communities reappear on stage, when they are consistently undermined, imperiled elsewhere - curating for International Theatre Festival of Kerala 2020. Jury: Satish Alekar (Acclaimed Playwright), Arundhati Ghosh (India Foundation for the Arts) and Zuleikha Chaudhari (Renowned Director)

Inverted Poem for Independence Day

Where the mind harbours fear and the head is held low;

Where knowledge is censored;

Where the world has broken up into fragments by narrow domestic walls;

Where words come out from the depth of lies;

Where tireless striving stretches its arms towards the unsound;

Where the clear stream of reason has lost its way into the dreary desert sand of dead habit;

Where the mind is misled by charlatans into ever-worsening thought and action;

From this hell of captivity, my people, let my country awake.

~ Rabindranath Today

Windows of Lament

Mashrafiya, derived from the verb shrafa, means to overlook or to observe. A mashrabiya is a window: one that projects outwards from the house, is enclosed with carved wood latticework, located on the second floor or higher, often lined with stained glass. On being asked about the significance of windows, a young Kashmiri theatre artist had once replied that they don't keep windows. There are windows yes, in the sense that all houses have windows, but their houses don't keep windows anymore. Over the last three decades, the deafening sound of shootings, guns, and bombings smashed their windows so often, that they stopped replacing the glass years ago. The stained glass instead gave way to rags, scraps, shreds, frayed clothes, old tablecloth, bullet-holed curtains, newspaper, and occasionally, bloodstained garments of family members killed suddenly by a stray bullet, stretched tensely across all windows.

A window for this young man was not a place to observe the world from, not one where the nature of modesty and imagination were considered, not even a divine break in the wall for light to pierce through. For him, a window was not a view to the world outside, but an agonising reminder of what's left of the house. He tried hard but couldn't ever bring himself to accept windows for what they are. He gathered a great number of broken windows of all kind, and hemmed them, hemming in a memory of an explosion. Today, on Eid, when all windows in Kashmir, and to Kashmir, are shut more than ever before, his work, created as part of a lecture I took several years ago, resonates with an even deeper lament.

Tiny Homes

If you haven’t experienced democracy in an ordinary form, in the everydayness of your life, chances are you don’t know what it means. Democracy is practice first, principle later. It is all very well to speak the language of rights and duties, of crime and punish, of votes and numbers, of allies and opposition, but democracy is foremost, before everything else, an inter-relational philosophy. While teaching theatre-making, one of my favourite exercises is called ‘Home-Image’. Students are asked to create a performed image of what home means to them. It isn’t as easy as it sounds. They are encouraged to dive deep inside, churn those memories, think hard and long about how they would crystallise their home into a single moment, a single enduring image; indeed dwell upon what home is. Nearly every piece displays a warm, affectionate place where they feel deeply loved (rarely not), but none I remember shows home to be, at its core, a democratic space. Home is shown as territory, as psychological, as physical, marked by how joy was cooked, in the pile of unwashed days on a stool, in its maternal odour, through its paternal voice, in its seasonal prose, to its undiscovered recesses known only to the dweller, the student. But seldom has the childhood home been narrativised as essentially unpredictable. This has been a source of immense bewilderment for me.

Home almost always is shown as being presided over by an authority, in body or spirit. In Indian households, perhaps more than any other, this authority holds itself beyond query, even the query of love. Think about the innumerable times you couldn’t question your father or mother for fear of being scolded, berated, shamed. Think about countless ways in which you needed to lie, hide, or flee lest you are punished, reprimanded disproportionately for something you did. Recall the unnumbered moments when you gave into their whims, to their symbolic calls of tradition and order, not because you understood it for what it is, but because their hearts would hurt if you didn’t perform as they said. Because their love for you would hurt. All these occasions are also opportunities for democracy to be practiced, for perspectives to be heard, for aspirations to be asserted, for confessions to be made, for hands to be held, for empathy and love to be truly shown, for dialogue amongst parents and children to take place. And yet the domestic space, the most intimate of all spaces, one which protects the dreamer in us all, one that profoundly shapes our souls, is also sadly a graveyard for democracy. Indian houses are characteristically furnished with affection, and are inherently undemocratic. If you cannot think of your childhood home as being constituted of all of you, of everybody’s poetry and prose, of occasional anarchy, chaos, and disorder, chances are that the authority’s rhetoric shaped your experience of home. Home is after all, according to Bachelard, the quintessential phenomenological object, meaning that this is the place in which the personal experience reaches its epitome. Home is charged with mental experience.

An Indian house is a final house, tethered irrevocably to an idea of authority. To be truly democratic, a home will need to be unforeseeable, even if this means that the future image of the home is impossible to be held together, especially in the dream of the patriarch. The more this authority inscribes itself into the home, the more this home wills itself into the architecture of the self. Homes, while being a source of immense emotional strength, also become over-determined spaces. Democracy and unpredictability go hand-in-hand. A decade spent in teaching has shocked me into realising that our young come from inherently undemocratic spaces, dragging their undemocratic selves to class, to art. It has made me realise that my childhood home was not an exception but a rule. In jest, I often ask my students to share an account of democracy in action from their lives, from their homes. Not when they go to vote, not during elections, not that farce where democracy is sabotaged and reduced to power brokering. I mean sincerely, from our wearisome common lives, give me an instance of democracy in practice. What follows is an awkward, painfully long silence.

PS. Which side you are on regarding the current crisis of our country reveals the complexity of your understanding of democracy, and the depth of your convictions.

Pic - Tiny Homes, Facilitated by D Gillian Turner, CVAG.

Fool All The People All The Time

When a politician mobilises the image of being an ascetic, or increasingly now, when a yogi becomes a politician, a fairly complex and seemingly contrary set of beliefs are put into play. I have always found it mysterious how Indian politicians and ascetics have swung both ways, with an unusually high success rate. Why does it work so well?

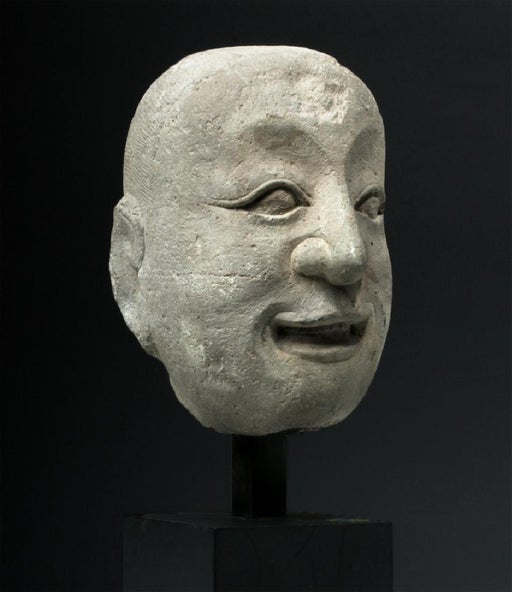

There is a deep seated obsession with the ascetic in the collective Indian psyche. If there is one psychological attraction that unites Indians across caste, creed, gender, it is a veneration for asceticism. In a largely conservative society that India is, the ascetic is allowed all manners of deviance. He is allowed to shed clothes without being charged for obscenity, be sexually indiscriminate without being considered immoral, amass limitless wealth without being identified with the wealthy, and permitted to perform acts and consume substances that others will be incarcerated for. The ascetic occupies categories of being without belonging to them, never shackled to them. In this sense, the ascetic is the truest actor; he does not believe in the ways of the world, yet continues to exist in dimensions of perception through which he must necessarily be experienced. Shiva is worshipped for being the greatest ascetic. Shiva is also the lord of performance - “Among the greatest of the names of shiva is Nataraja, Lord of Dancers, or King of Actors. The cosmos is his theatre, there are many different steps in his repertory. He himself is actor and audience.” (from Coomaraswamy’s The Dance of Shiva). Aptly, the new academic session at National School of Drama begins with an ode to Shiva every year.

The adjective "ascetic" derives from the ancient Greek term askēsis, which means "training" or "exercise". The original usage did not refer to self-denial, but to the physical training required for athletic events. Athletics of identity? Athletics of personhood? Athletics of ethics, of politics? In his essay ("What Do Ascetic Ideals Mean?") Nietzsche discusses what he terms the "ascetic ideal" and its role in the formulation of morality along with the history of the will. ‘A paradoxical action as asceticism might serve the interests of life: one can express both ressentiment and the will to power’ he wrote. Are these the opposing forces that hold the figure together, the impossible figure of the ascetic-politician? To be an ascetic-politician is to inhabit a paradoxical state, to harbour both a hostility towards power and a craving for it. The more intensely taut these opposing forces become, the more powerful the figure conjured by the ascetic-politician becomes. The actor, the ascetic must perceive the world for its lies, yet continue to perform in the ways of the world, to cease attention from people, to move them, to win them. This is the paradox and surprisingly the currency of the actor-ascetic-politician. To evoke a psychic attraction of the people in him, the politician must be seen to renounce power, to attach to it no meaning, little value. This he must do to be able to finally cease power. This is the allure of Gandhi in his politics of exemplarity. As Pratap Bhanu Mehta puts it, ‘In times of crisis the question to ask is not what ideology, what party, what collective action? The question to ask is: What makes political action an exemplar that is credible in the eyes of others?’. Gandhi increasingly adopted the artifice of the Mahatma as he grew more popular among Indian people. He routinely declined offers to hold political office; the more he appeared to renounce obvious power, the more his aura acquired actual power. To preserve and expand on ascetic power, he must be seen to lead a life of abstinence, he must be seen to ‘un-belong’ - belong not to the government, not to his family, never to himself. To keep him poor was an expensive affair, a congress person had muttered casually once. For Indians, this is what sets Gandhi's legacy apart from his contemporaries like Nehru, one whose intellect and vision is increasingly discredited by citing his penchant for power and pleasures: relishing in coterie, indulging himself with parties, amorous friendships, and occasional dancing.

Our current politicians understand the alluring power of an ascetic all too well. They know that there is a culturally admiring, spiritually obeyant Indian psyche out there, which has been nurtured to revere the ascetic over centuries. And this is what the current political regime deploys as their most powerful weapon. The exemplary aspect needs to be on steroids to marry this symbol to communicative capitalism of 21st century. Welcome the three A’s of contemporary Varanasi- Adhyatma, Aastha, Aadhunikta (Spirituality, Faith, Modernisation). The ascetic-politician must hold these seemingly contradictory identities in the image of the people to gain absolute power. He must be seen to wield the modern state's power during the day (strong speeches, war mongering, paired with taking ostensibly bold actions), and be seen as a peaceful sage at night (meditating monk in a cave, on a pilgrimage barefoot, giving interviews that invoke a narrative of abjection, privation of material and appetite). He must be seen to be celibate (disown his wife), abandon regard for his family; he must be seen to work selflessly for the people, but never desire their admiration, always welcome their vitriol. By casting himself such, the ascetic-politician makes himself immune to all criticism that call his bluff. Infact, the rallying call of opponents pointing towards the inherent falsehood of playing both an ascetic and a politician - circulating memes disdainfully comparing him to self-serving film actors - only emboldens the image of the ascetic-politician as a true actor. An actor who everybody knows is only playing a part, never whole himself.

The central character in Shrilal Shukla’s novel Raag Darbari is Vaidyaji, the pivot of power in the village, one who exercises unrivalled control over panchayat, local elections, cooperative society. How? By being seen to detest it. By being seen to relinquish all desire for holding office or rank. Yet, he is able to amass unprecedented power in his hands, routinely spinning a web of rhetoric through spiritual platitudes, quotes from Sanskrit texts, and his penchant for whipping spontaneous aphorism. He is your ascetic-politician embodied, who will never insult his audience by speaking the truth, but will always appear to be acting truthfully. He never utters a single unethical word, not even in private, and yet he rules through the immorality of his soul. Vaidyaji is faced with the ultimate question of power in the end - how to build an enduring legacy. After all, legacy is ultimate power. More than wealth, wide-spread respect, or place in history books, more than anything you can imagine amassing in a span of a lifetime, to die a promised death, the promise to inhabit the collective conscience of all Indian people, and of all coming generations, to be immortal. A politician can live forever in the robes of an ascetic. This is how you get to live in India forever. This is how you fool all the people all the time.

Pic - Lohan the ascetic (sculpture or mask?)

Violence Tax

As we all rush to file our taxes before the deadline, a well meaning accountant-friend is puzzled by an absence of stock portfolio. 'Why do you not invest in stocks & shares?!' he asks. 'The stock market is fascinating" I reply in my defence, 'It is perhaps the cruelest and consequently the most precise manifestation of what the market does, which is to serve a heady concoction of 'feelings''. He is unmoved. 'You see, when you invest in stocks, don't invest in companies, invest in events.' he declares. 'Events?' I look puzzled now. 'Yes, events. Like invest in stocks when elections arrive. Spot the companies which are associated with the political party most likely to win elections. Invest in them. Or, when floods hit the country. Invest in cement companies, you can make money in a month's time'. I am shocked. I am frozen.

Basically, I am being given advice to help fascists govts come to power, or to make profit from catastrophe that hits millions of people. I suddenly remember P. Sainath's lucid lecture on Crisis Economy, about how the stock market encourages big financial players to make profit out of crisis. To think that ordinary common people have also begun to mimic these attitudes unthinkingly is a whole new revelation. Imagine the scale at which this operates now - millions of small investors putting their money in 'events' that are a direct of consequence of political violence, natural catastrophes, social adversity. This mass-scale habit of investment needs to feed off disturbances, needs its 6.75 percent growth from disasters and distress.

This is the mirror opposite of people voyeuristically holding their phones up to film an act of violence for pleasure. This is the trope that is borne out of disgusting instances like mob lynching, where the lynchers find a tacit consent from society to carry on with violence in their name. I look at my friend, who sits diligently working across spreadsheets putting taxes in order. Tax-on-violence is the new nation's income. I sit across the table, horrified.

On Being Quoted Online

Little did I know that rambling about my work will enter the dictionary one day to explain the usage of the word 'immersing'. That's it, I should stop talking.

https://www.definitions.net/definition/immersing?fbclid=IwAR0pjjin71knu2c1VGnF4nO_0if-Ztkb_gdaBOHSZ09KGc6K8fODpdKQo28

Theatre Appreciation Course

Most likely the last year that I will curate the Theatre Appreciation Course at NSD. It has been a delightful run spanning a decade, and how the course has grown! The only course of its kind in the country, we inaugurated it in 2010 to address dwindling audience numbers and a shocking absence of informed appreciation of theatre. The course received a modest 50 applications in the first year, and they were up to 600 last year! A total of 500 participants - writers, researchers, journalists, curators, teachers, aesthetes, theatre enthusiasts, IAS officers, engineers, doctors, police officers, home-makers, retired persons, college students, activists, artists, and many many more - have attended the course so far and found it immensely valuable. Through the course, I have had the good fortune of meeting several brilliant minds from all walks of life, and I hope the upcoming edition will bring yet another exciting group together. The experts we are able to invite, the theatre archive we are able to mobilise, and the scale at which we hold the course, is only possible at an institution like NSD. Apply, apply, apply!!

National School of Drama (NSD) invites applications for the Theatre Appreciation Course, to be held in NSD campus from May 27-June 04, 2019. This cross-disciplinary course will critically examine the formation of contemporary theatre and its multiple histories, forms, ideologies and locales. The course offered attempts to familiarize participants with practices, genealogies and methods that help analyze the contemporary with reference to the ‘local’, ‘global’ and ‘international’.

To this end, the course has been designed as a combination of lecture sessions conducted by renowned thinkers and practitioners, followed by group discussions, video modules and viewing of live performances. The lecture inputs traverse a range of topics such as ‘modernity’, ‘tradition’ and ‘popular’ in performance, the classical, its formations and challenges, how theatre practices interface with literature and media. General introduction to stage lighting, costume, back stage auditoria and documentation practices position the notion of materiality of theatre practices at the forefront of any discourse on performance. In addition to this, to encourage writing on theatre, workshops on theatre criticism and playwriting may also be held simultaneously for interested participants. This is an intensive course for which reading material will be made available. A participation certificate will be awarded upon successful completion.

Last date to submit your forms - May 15, 2019. Forms are available at NSD reception on all weekdays from 11am-4pm. They can also be downloaded from NSD website:

<https://nsd.gov.in/…/application-invited-for-theatre-appre…/>

Survival/Election

The ingenuity of displaying Hindu gods behind you on the wall, not only because you believe in an abstract idea of inter-faith admiration, but because you also hope to deflect an angry mob, and steal that precious extra second to flee, when communal riots erupt. Nawaab Saab, an excellent muslim tailor, who earns a meagre 300 rupees a day, sitting and stitching on a street in Delhi, fears for his life in these elections. It is only fair that his face be protected by a Hindu god in this photo too. General Fear elections 2019.

ITFoK Artistic Director 2020

Honoured to be nominated Artistic Director for ITFOK 2020. This international theatre festival of Kerala is one of the most exciting forums for theatre and live art in Asia, one that has been built together by theatre persons, writers, poets, arts programmers, and the state government over the last several years. Like me, many of you have been visiting ITFOK to perform, to participate, to speak, to watch new works, and to meet friends and colleagues. What a delight it will be to help shape the upcoming edition. Look forward to this exciting year.

Submissions are now open. Please apply and spread the word -

ITFOK 2020 Theme - Imagining Communities

In the age of weaponised fake news, disinformation, and unceasing attacks at the idea of culture, what should the role of art and theatre be? Should theatre bring us to ‘see the whole’ again, act to re-construct overdetermined categories of community, society, and the nation? Or should it continue to disrupt these ‘imagined communities’ by reassembling histories, by performing new alignments, calling forth new communities? ITFOK 2020 will mobilise ‘forms’ to stage this transitive contemporary. It will seek to reflect upon the state of democracy, call attention to alternative voices, and propose different futures or ways to remember. In this spirit, all kinds of performative works are welcome - proscenium plays, performance-readings, live art, promenade theatre, follow-art, site-specific theatre, game-narratives, endurance-art, documentary-theatre, intimate-plays, lecture performances, flash-drama, theatre-on-the-internet, or any other work that experiments with participation, interaction, and the political urgency of live art forms. The intention is to employ the theatric to form a community of interest, to imagine new geographies of space, of body, and of the mind. ITFOK 2020 will imagine our theatre as a deep, horizontal comradeship.

https://theatrefestivalkerala.com

On World Theatre Day

Why is Theatre on the UNESCO International Days list? One look at the list of days set aside by UNESCO for commemoration, and you’d realise something is odd. Environment, Ocean, Indigenous People, Democracy, Peace, Philosophy, AIDS, Persons with Disability, Migrants, Press Freedom, all have their commemorative days. Each one of these ideas and/or communities are under constant threat, and understandably need an annual reminder to continue efforts for protection and preservation. No other art practice finds its mention on this list - no Cinema Day, no Fine Arts day, No Music Day (ok there is Jazz Day). So how come Theatre landed up on this list? Is it endangered, does it need protection, or perhaps resuscitation? Does it need a constant reminder that doing theatre is a Human Rights Issue (itself already on the list), that any collective act to self-determination and self-organisation is, in its very essence, an act of rehearsing the community.

Theatre has historically debated and expressed each one of the concerns that find themselves on the UNESCO list. If you’ve watched plays, you have most likely come across a play that privileged the marginal voice - the migrant’s, the worker’s, the child’s, the woman’s, the jester’s, the tramp’s, the poet’s, the philosopher’s, and countless others who occupy the periphery. Yet, the very medium in which the margin finds its voice, is itself on the commemoration list. This is twice marginalised then - talking about the margin while being one. And I think this is a beautiful space to be in. We need to celebrate Theatre everyday, fill our streets with everything that is marginalised, bring them to occupy the centre, even if temporarily, everyday.