Electronic City (2007)

KS

Deeply shocked to know about Prof. KS Rajendran’s sudden passing this morning. Many on my timeline have been his students, as have I. From a teacher of Classical Drama, he had, for me, transformed into a friend over the years, rarely hesitating to speak his mind with me. He was an audience to my first professional theatre work back in 2007, when he decided to accost me right after the show to say, “I have been resisting the onset of the 21st century, but having watched your work, I don’t think I can hold out any longer.” Speaking in his characteristic tone, it was, as usual, hard to tell where his comment had landed —did he say what he said in appreciation of what he saw, or, in a grudging admission of the times in which the work was made?

He taught Classical Performance at the Nsd for over two decades with skepticism and curiosity. He started his lectures with quintessential doubt in the way in which we discover, narrativise, and resurrect the past. It was a delight to hear him admit about how little he really knows, as a professor, about the Classical Arts, where his national colleagues wouldn’t tire painting the past with certainty and glory. He was a prolific writer and a sharp, considerate editor. It was under him that several Nsd publications saw the light of day spanning a decade of rigor and new insight.

His post-retirement years brought us closer, when he expressed his wish to spearhead workshops in theatre direction (an occupation rarely considered an art practice) and I was most happy to help him make it happen.

He was a glamorous smoker, a master of self-deprecating humour, a staunch believer in an institution with an open-door policy, and a reluctant teacher. You will be much missed, Sir.

Back To School

Schools are reopening from tomorrow in-person after nearly two years of running online. This photo is from a day last December when a wildlife photographer came to online class and asked everyone to imagine the enormity of an ocean. She asked this little one if a blue whale might fit into his house, and he said it might, but we’d need to invite the ocean into the house first.

House Hack

I grew up with a house hack that turned the morning newspaper into more useful things as the day marched on. The newspaper was folded and laid across the breadth and length of shelves in the kitchen to help soak up wet utensils; it was used as an added layer on shoe racks to catch the dust falling off the soles; it was used to wrap old gifts that had outlived their occasion and might never get opened for use; it covered new shiny steel utensils that were only just bought and kept aside for that special festival cooking; it was pasted on a part of a crumbling wall to dry out a damp patch (and buy us enough time to earn the money to fix it); it was used in craft classes to stuff dolls with, or, to pack handmade puppets with; it was what lit our bonfire on cold winter nights, and, the first thing we laid our hands on when we opened the morning doors —the newspaper was everywhere we looked and lived in the house. But, news never overwhelmed our world, it rarely entered domestic conversation.

Today, there isn’t even a single sheet of newspaper in the house. And yet, somehow, news today has a cunning, crafty, oppressive power over us, the kind it never had all those years when it lived quietly amidst us.

LOR

I have written a little over 50 letters of recommendation so far. I often request younger people to keep me as their last option; I encourage them to find people more established and senior in the art field, experts whose names will add that prestigious weight to paper. Some successfully find a prominent name for their purpose; others who, for one reason or another, fail to do so, come back. I prefer to only mention about their work which I have personally encountered, but even so, I struggle to keep the letters brief. And this is because I often can't resist writing about the beauty of promise that I find in the work of young artists. I find it difficult to contain my excitement at the surprising revelations nestled in a student's work; I can't stop myself from imagining the glorious possible futures of their creation which exists, at the moment, in the form of an unglamourous student exercise in a small classroom.

The LORs that I begin to write threaten to transform into a personal letter to them, the opening pages of a private dialogue -- from tutor, with love -- because their artistic explorations gave me something precious, moved me in profound ways. I write for them, but really, I am writing to them, thanking them for their creations, for sharing the depths of their existence (abyss and all) with me.

But then, I stop myself short from doing so. Because I know that LORs will eventually land up in a heap of hundreds of them on some administrator's desk or in the hands of a tired panelist looking at dozens during an admission process. It would be a pity for private correspondence to get lost among letters masquerading as "positive letters, that confirm that you believe the person is a strong candidate for a course/university/academy with no reservations whatsoever."

Of course, they are.

Old Year/New Year

I learnt this year that soccer can be played to an empty stadium; they played cricket like that too, but it was only half the sport. I learnt this year that some summer plants can survive the winter, and they can do this quietly, in their own secret ways. I learnt that a child grows like sunlight does; he is advancing and expanding in ways that are imperceptible to me. I learnt that friendship is possible with my past companion, and that it is necessary to resist the hubris of legalese that demands conclusive endings. I learnt that if you get close, a teardrop resembles a snowflake, but get closer and they become unique works of art. I learnt that ageing parents, as they get frail, are still more resilient than they appear to be. So are newborns: they find life, life finds them, always.

I learnt this year that congratulating someone on a big life event — someone I’ve never met in person, or don’t know anything about — matters more than I previously thought it did. I learnt that single parenting is every bit as hard as they say it is. I learnt to console my grieving beloved with my voice only: Phone is all we had keeping us held when the pandemic snatched her parent from her. I learnt that living in the age of screens aggressively demanding my attention, it is still a window that shows what is most precious to view. I learnt that butterflies need a proper burial, that last rites do bring solace; whether you keep faith in religion, or don’t, has nothing to do with it. I learnt that words have the kind of life you breathe into them; you can make them light as air, you can pollute them with insincerity, you can cleanse them with vulnerability.

I learnt this year that I still applaud when they send a rocket into space; the sheer scale of the unknown out there thrills me no end. I learnt that "falling in love" doesn’t describe what actually happens when hearts entwine; it is more like a forest that grows into feelings, or, feelings into a forest —what’s the difference, really? I learnt that I often forget what I learn, that I forget I forget, and occasionally, I can’t tell if I am learning something all over again. That’s how, I have come to believe, it works: forgetting is a part of learning, as are several years a part of a single one.

I learnt, long ago, that new year resolutions are useless, that the turn of a year is really only a date, but continuity needs punctuation to make sense.

And so, into another year, from this year, I go.

BrownSpeak

The hypocrisy of Indian celebrities tweeting hashtag-blacklivesmatter, while not paying any heed to injustices in India, is perhaps a symptom of a deeper malaise that infects the brown mind.

Art practice has taken me to foreign lands in the last decade and to stranger experiences; artistic studies, research and residencies are often unpredictable, poorly managed, sometimes unassisted, and need to be endured alone, occasionally on subsistence level support. You have to learn to adapt to a foreign land quickly - with it or against it - to be able to make your work. To do this, you begin by catching the scent of people who live against the existing order. Every society has common people who live, to some extent, outside, in opposition to the system. Not just the natives, but the diasporas too. I have met some lovely folks - Slavik, Japanese, Swiss, Australian, Nigerian, Lebanese, Russian, Brazilian - engaged in one manner of subversion-living or another in several parts of the world. One diaspora I have sorely missed encountering in these realms is the Hindu Indian diaspora (henceforth HID).

In every part of the world I have temporarily lived in, the HID has not just been shockingly absent from the world of subversive politics and action (let alone from the world of art and theatre), but in sharp contrast, has avidly towed the line of the hegemonic culture like no other. It was a rare sight to spot the HID student in foreign universities I studied at, and later taught in. The HID is not in attendance in theatres and exhibitions either, not the ones I have traveled to since. I can accept that it was simply a matter of luck that I missed them, but it isn't luck if it runs out not even once.

I have often been told that white culture has intentionally kept non-white communities away from participating in urban western culture, and while this was largely true, it also drove the non-brown communities' need to perform subversions in their own right, which they did. I have been told that brown communities migrated under dire circumstances and inhabited poor neighbourhoods, but we also know that the richest minorities in several parts of the world today including U.K., U.S., Canada etc. are brown people, especially HID (watch Netflix’s Sex Education and you’ll know what I mean). When despite having clinched better lives by migrating to better lands, brown communities do not, as a rule, engage with their surroundings in politically alert, intelligent, subversive ways, we need to ask the question - is to be brown to be apolitical?

The HID is occasionally seen as aspiring to white culture, both from within the community (the racial slur “coconut”) and without (its cowardly abstinence from solidarity movements against white discrimination). Is to be brown to be inherently discriminatory; an identity that is borne only in and as an act of discriminating against others? Even in lands foreign and free, it is rare to come across brown families that aren’t conservatively structured, that are not ruled by the iron fist of the traditional patriarch and not assembled as a heterosexual hierarchical tiered house. Is to be brown to be shackled to oppressive notions of power and control? The HID is seen repeating the vocabulary of safe and unsafe neighbourhoods in the voice of the hegemonic class, instructing their children to avoid places where non-whites live - Is to be brown to be committed to erasure of oneself in the image of the "higher" race, only to replace them when they leave the spot?

Today, HID is being rightly called out for silently supporting anti-blackness and hatred towards black communities. Today, HID is justifiably being asked in real terms: do you have any real or concrete thing to offer to humanity? Will you stand in unconditional solidarity with People Of Colour? Will you call out discriminatory practices across the world, especially in India? Today, HID will need to reckon with the casteist, racist and islamophobic world of their elders, and for once, contribute their own recipe towards a cultural and social revolution. Really, the time for this new "curry" is now.

Tenderness

Re #boislockerroom: It was in grade VI when I got pulled into a gamble around genitals. ”If you buy me ice-cream, I will show you what’s under my pants”, the boy sitting next to me said. It came as an abrupt invitation. No-one had quite put it like that before; going nude for icecream? He was the class’ blue-eyed boy, and I had only just joined in. To get to sit with him was a matter of early-teen prestige which I wasn’t willing to throw away easily. To keep him, and my seat, I conceded. He dropped his pencil, and when I bent down to pick it up, he grabbed the end of his shorts, snuck in his hand, pulled his underwear away, seized my head and made me look all the way up his thigh. It seemed that neither one of us knew how long this moment should last, but it felt like I was down there till my neck hurt. I came back up unsteady, and struggled to shed from my vision what I had just seen. His genitals were glued to my face now. No matter how hard I struggled, I just could not cast them away. They stayed on, as if pinned to my forehead, for the entire class, then the one after, and another. Teachers came and left, but I couldn’t tell what went on the blackboard. His dangly bits refused to leave my face till hours after we got to lunch, to the canteen, when he made me buy him his icecream. It was only then when I finally understood why he did what he did. He sat licking his prize narrating how he had won it, bragging to friends around. He managed to make me the butt of his jokes. The class spent the entire lunch admiring his ‘dare’ and laughing at me, and it was probably for the first time I felt shame. I didn't know where to look, I didn't know what to say. This was my welcome to adolescence; a brief, sudden, unwanted peep show. It felt dirty, so filthy and so ugly.

Two decades, and several experiences later (a large portion of which was spent listening to horrid stories of unspeakable sexual abuse that my female friends had suffered, survived, and had grown up to talk about), I read the play UGLY by the award winning author Christos Tsiolkas. It is a sketch of frustration through the lens of a high-school drop out who commits a seemingly senseless act of violence under the headiness of masculine toxicity. I read this play along with SLUT, written by the acclaimed playwright & novelist Patricia Cornelius, which takes its cue from a horrific real-life teen shooting spree incident. She generates a fictionalised history of the killer’s ‘lover’, dubbing her ‘Lolita’, and speculates on what kind of personal story might lie behind the tabloid label of a ‘party girl’.

In a special note to me, Patricia wrote how she went to various schools (in Australia) to talk to young people about gender, and how she learnt that some things don’t ever change - “When a girl is overtly sexual, she is diminished, disregarded, sneered upon. Her best friend will drop her, boys will think of her as “an easy lay”, the world will have no sympathy for her no matter what happens to her - she would have brought it upon herself, she would have deserved it, and she would be the cause of it.” Adolescence and sex is a minefield.

Interweaving the two scripts, I created the play Tenderness (2012). The intention was to unpack issues of race, class, sexual-preference and the role of social media. Along with the student-actors, we brought to rehearsals several teenage testimonies of committing crimes that are assessed as cases that are ‘deviant’ or ‘individual’. Contrary to perception, the teenage world is often disturbing and macabre, where notions of gender, sexuality, love, aspirations and hate create a world of disorder and chaos. In the play, the characters performed an intensely contested ‘body’ between locations of childhood and adulthood. How teenagers navigate this journey shapes the kind of adults they become at the end of it. Does being a teenager necessarily mean to be 'volatile’? Is it to be read alongside normative notions of childhood development where we go from being child, teenager to adult in some kind of ahistorical vacuum?

Bearing its content in mind, the play was given an ‘adults only’ rating. This was ironic, because the play was about teenagers, for teenagers. Who can watch and who cannot is a funny business in India, and I am rarely able to point towards the maturity behind these judgements. On the day of the third show, a mother arrived to watch the play with her two teenage daughters. She admitted that she was aware about its explicit nature (her husband had watched the play a day before), and had decided that it was relevant for their daughters to watch it. This was a play with scenes in which teenage characters spoke about things any Indian parent would scowl at them for. The mother persisted at the door and eventually fought her way in. She sat sandwiched between her daughters. She kept talking to them throughout the play; they laughed, they were aghast, they shared silences together. The mother hunted me down after the show, shook my hand, and said “I couldn’t have had this conversation with my girls at home.”

How we talk to young boys and girls about these issues also shows what kind of adults we are ourselves. The play ended with these memorable lines, which somehow capture the slippery turf that is adolescence.

“We were trying to get to this place—it was me and you, I think, and some other people—and it was a little like my house … Although, well, it was my house, but it didn’t look like my house, somehow. And we were trying not to be seen.”

Parenting In The Times Of Crisis

Last October, my son woke up to the news that his play-school suddenly shut in response to the rising air pollution levels in the city. In December, his school shut doors again, imposed by curfew during the crackdown upon two of city’s universities. Another unscheduled shutdown occurred in February, when the school was in the grip of fear from the week-long rioting, killing, burning, looting, and unspeakable violence which engulfed our neighbourhood. And now, in March, they closed doors again, this time for an unprecedented duration in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. A log of unscheduled school holidays has become an excellent way to keep a record of catastrophes that have besieged our world. My son is only three years old, and he is learning more about the world by being made to stay away from school than by being in it.

For their part, the play-school is working on the double, sending mails daily, enlisting activities which children would do at school had they been there. Many parents find these tips helpful; if you’ve spent a whole day with a kid and not run out of ideas and consequently out of your mind, you’d be lying. Still, there is something amiss about nudging parents into hosting school-at-home. I imagine the role which a structured school plays to be different to what parenting does at home; they are to my mind occasionally at odds with each other. School is where kids learn to be with others, where they acquire social knowledge and skills. I reckon home is a place where they explore the contours of an evolving interiority. School has unquestionable hierarchies in place – teacher/student, senior/junior, serious/play. Home could have blurred, fluid boundaries, a space never final, never symmetrical in relation to all that is in it. School is determinedly structured, while home could be kept spontaneous to the extent that it can be, so that kids feel free to indulge in a reverie not bound by a timetable. My son has his favourite window, his mornings and evenings are spent there simply gazing outward till I hear him sigh, which usually means that he has had enough of the outside world. I imagine parenting at home to be an unrehearsed duet with school, knowing very well that we need to synchronise our efforts for consistency’s sake, but every now and then making sure to spiral away on our own paths as well.

What is even more unsettling about the anxiety to complete pre-designated school activities at home is the signal that is being sent to children – that all is ok, that they should continue learning like they would in a world where everything is proceeding as planned, where all is well as long as they finish school-work. Parents obsessively concoct all kinds of juvenile stories to explain to their curious kids why their school is shut, and why school-work must be attended to by putting blinkers on. The world outside is considered a distraction at best, a panic-stricken reality at worst. Don’t get me wrong, I am not advocating that we expose our children to the world’s horrors before they are ready to face them. Although how would we know what exactly is the right age? The age appropriate mark at which ‘exposure’ to such things takes place is getting progressively younger: one look at Greta (Thunberg) and her ilk of young climate warriors is convincing enough. But I do wonder if the unscheduled and frequent shutdowns are opportunities for us to reconfigure what kids’ “activities”, “learning outcomes”, “bedtime stories”, “age-relevant tasks” can mean in a crisis ridden world.

Early childhood is more mysterious than familiar. In her book The Philosophical Baby, Alison Gopnik, a professor of psychology at the University of California, Berkeley, argues that our mental development is more like a metamorphosis than an incremental process of growth. We as adults can boast of precious little understanding of how our kids’ minds transform. When my son plays, he knows he is just playing. Yet, play for him is a very serious business, where he gets to invent rules, and appreciates being asked how it all works. I love indulging him in playful immersions, in freely conjured hypothetical worlds, worlds of crisis even: ecological, gender, or his favourite parking crisis. Gopnik states that the luxury of a uniquely long period of childhood helps children to explore the world with unbound imagination, which in turn aids them to learn the ways of the world. She describes, for instance, how small children’s grasp of fantastical situations enables them to imagine alternative ways to ‘be’ in them. Children between the ages of two and six invent “invisible friends” who seem to help them learn how to interpret the actions of others. As if following the script, I recently noticed that my son has invented an imaginary friend too, a Dusky-leaf monkey who often falls ill, and how this is making him better at predicting the thoughts and feelings of actual people around him.

It is a common fault to regard small children as irrational and immoral. They drive parents up the wall by asking simple questions ad infinitum, questions which have obvious answers, or so parents believe up till they find themselves being pulled into the question’s philosophical quicksand (“Dad, why can’t I see my eyes?”). Gareth Matthews, a professor of philosophy at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, proposes that young children be regarded as “natural-born philosophers”. Other scholars have followed this line of inquiry to suggest that children, as young as two, are able to grasp the difference between moral rules which are intended to avoid harm (“don’t hurt others”), and merely convenient regulations (“take off your dirty shoes outside”). Is it any surprise then that the famous German philosopher Descartes had developed a strong bond with his daughter early, and another accomplished philosopher Bertrand Russell ran a school for young children? Jiro Yoshihara, a Japanese artist, often drew inspiration from children’s art and gestures to create his experiments with conceptual and performance art. In How to Raise a Child, a young Susan Sontag jotted down 10 rules she arrived at, one of which was never to discourage childish fantasies. As a mother, she harboured a subtle but palpable admiration for the precious gift of “childishness”. Fate returned the favour; her son David Rieff colluded with her fantasy that she wasn't dying, and went on to write a tender account of her final illness recounting how he ‘played along’ before she passed away. Children make worlds out of dreams and failures of that which surrounds them. It is necessary that they are encouraged to embrace the messy realities of the real world in their wonder, for it is the make-believe play that helps them comprehend and reshape the world they grow into.

We are stuck with parenting in the times of crises, and I doubt if we are prepared for it. Our children might make profound sense of the tragedies that have befallen us today, that which keep them home. We need to find meaningful ways to translate the beauty and disasters, the joys and failings, the triumphs and sorrows of our world for their pretend-play, and for their sake, stop pretending as adults that all is in order. Perhaps we can find inspiration by calling to mind a scene from Duck Soup by Marx Brothers, in which Rufus T. Firefly (played by Groucho) grumbles about as he is handed the cabinet’s treasury report: “Why, a child of four could understand this report. Run out and find me a four-year-old child, I cannot make head or tail of it.”

Privateness of a Hobby

Humanity has arguably spent longer time staying indoors than being out under the blue for the first time in history. And so, the privateness of life has crept up in ways stranger than before. It lingers around, while we have simply nothing to do. Being born and brought up in a culture that is unreservedly extroverted doesn’t help; from architecture, familial living, to seeking triumph in numbers, clustering is a social grammar everybody speaks in the subcontinent. Crowds are the place where everybody finds themselves. Even those who would not describe themselves as outgoing cannot deny that the sudden disappearance of public is unsettling, the abrupt retreat of noise is deafening. The subcontinent on a good day is a clamorous place.

The way I see it (hear it rather), clatter is loudest about drumming up stereotypes. Indians shout out stereotypes like it is native tongue; Punjabis are a jolly bunch, Bengalis have embarrassing nicknames, Tamilians are nerds, Malayalis are Madrasis, all Gujaratis want is an American visa. By and large, Indians are poor but happy, eat curry, worship many gods, and will avoid a confrontation. Stereotypes can be true and false at the same time. But what a stereotype cannot endure is interiority. A stereotype is a flat surface which, when invested with privateness, surrenders to depth. Not one stereotype about Indians that I have heard I found remotely interesting but, for what its worth, there is something else, which is curiously common to us all - broadly speaking, on the whole, Indians do not keep a hobby.

Hobbies are of many kinds; knitting, singing, learning something new, doing something together, these are all perfectly legitimate pastimes. But the ones I find missing are dogged pursuits; collecting, making, tinkering, or doing something routinely, as a matter of personal commitment to oneself. An activity that brings joy on its own, one that thrives without exposure or pay for years on end. An activity so private to you that others need to earn their way into getting a glimpse of it, into what keeps you engaged and away. To have a serious hobby is to claim a private life, the kind in which you take pleasure in doing something for its own sake. Make a small world of your own, and spare it the burden of purpose. To have a serious hobby is its own kind of rebellious act, small but not an insignificant one. ‘What’s your hobby’ is a staple question in job interviews, but no one has ever answered it with any detail or passion; has it ever been asked out of genuine curiosity?

Rare as they are, I know a few serious hobbyists. There is an elderly couple who spent their entire lives working in a post office, and pursued a committed hobby of making puppets. They created hundreds of marionettes, hand-, finger-, shadow-, puppets of all make and kind, only to dump them in the attic at the end, not one was ever meant to be on display! There was a neighbour who looked after an antique shop, and built doll's houses in her spare time. She was an incessant carver, kept a knife that sliced and chiseled away at hand always. She built over 500 wooden houses, each no less beautiful than the other, and left them at strangers' doorsteps because she had run out space to keep them! But perhaps the most eccentric hobbyist was closer home. An uncle of mine had a secret love for train-models. He started small, scrapped countless versions early on, till he hit upon a way of scaling it up. He built a terrace shed faster than he built a home for his fledgling family underneath. The room above, in its final version, was a model spread over 100 square feet, with cork, foam, metal file, control circuitry, multiple tracks, trees, rocks, tunnels, bushes, roads, bridges, houses, diorama, and water flowing into the cleaning sheds, all soldered by an amateur hand, everything in miniature. He devoted to it countless hours, and at one time, all his savings!

Privateness of the kind that a serious hobby is, is almost entirely missing from the subcontinent. The exceptional few who have managed to nurture this purely private liberty are perhaps doing better than most at surviving these bleak times indoors. For the rest of us, I wonder if we are a people who never give any serious thought to who we are when we are not with others. I wonder what is it that we do when we find ourselves in our own company. What is it that we do if we do not keep a hobby?

(PC: Lucerne Museum, Personal Allbum)

The Great Pause

The Great Pause - When everything stopped, when tragedy struck, when we couldn’t believe it. The Great Pause - when birds came out, when people died, when a pangolin breathed. The Great Pause - when cities went quiet, when houses weren't enough, when they had to walk. The Great Pause - when TV showed reruns, when millions went hungry, when no doorbell rang. The Great Pause - when the earth stopped rattling, when everyone kept away, when they remembered everyone. The Great Pause - when air became air, when we set miracles aside, when doctors toiled and prayed. The Great Pause - when windows became enchanted, with plenty under the sky, when each one was sacred. The Great Pause - when speakers stopped lying, when religion didn’t matter, when we cooked for each other. The Great Pause - when the mountains appeared, when the world was out in plain sight, when we had to believe it. The Great Pause - when everyday became that day, when we got the chance, to start again. The Great Pause - when we hurt, when we waited, when it was all too profound.

Image: Fulton Center station in Lower Manhattan, New York City. Alan Taylor for The Atlantic (March 18, 2020)

Nurses

Nurses know something deeper about our bodies than we do. They know something different about healing, about the practice of healing, about the patience and perseverance in healing. What nurses know about care giving is different than what doctors and families do. This one from Kerala, a nun in her previous avataar, had nursed me back to health in childhood when I fell terribly ill for the first and only time. I wouldn’t allow any doctor near me in her absence; I needed to see her face, hold her hand, the hand that secretly offered candy. She was unsentimentally affectionate, something about her grace made me feel brave. Nurses are the people I remember from my visits to hospitals since. I admire the ones who are dispassionately efficient, but those who have unusual access to the depths and shallows of the human condition in sickness are the ones I never forget.

I recently discovered that nurses have been poets too. In ‘The Poetry of Nursing’ (edited by Judy Schaefer), nurse-poets write poems and commentaries on life and death. Here is one who writes about touching, the only sense that is forbidden in the times of the pandemic today - ‘I took a long look at my willingness to touch and be touched. I understand the professional prohibitions. Yet, this moment of touching and being touched was a healing one’ - Lianne Elizabeth Mercer. Nilima Sheikh refers to her words as part of a tribute to nurses in her recent showing ‘Salam Chechi’ at Kochi Muziris Biennale (2018, painting below)

It is heartbreaking to see that health care workers are living in the face of fear today. They should not have to beg for personal protection equipment, they should not have to put out appeals on social media, they should not have to work knowing that being infected is inevitable, knowing as we all do that it is preventable. On the frontline are nurses today performing extreme shifts in isolation wards (no meals or bathroom breaks allowed). In China, the epicenter of the outbreak, more than 3,300 nurses and health care workers have contracted the virus. The number in India is rising now. Governments are scuttling between vendors for PPE supplies, trying to outbid each other, and I desperately hope that all this is not a tragedy unfolding. Every single nurse out there, every single health care professional deserves to be protected, and it is our ethical duty to demand that this happens.

How I Became An Atheist

For all that this pandemic has and will make humanity do, what it has achieved distinctly is this - it has rendered the planet spectacularly godless. I don’t think we have come to publicly admit that we are in the midst of an unprecedented wave of atheism. Places of worship have shut down, messengers of god are entirely out of business. Scientists, doctors, nurses are our everyday messiahs, doing what gods do had they existed- put themselves at risk to save humanity. It is the perfect time to contemplate not how God arrives (or leaves), but how profoundly godless our world is.

Like much else in life, godlessness came to me through a play. In my early 20’s, I voluntarily signed up for an undergraduate lecture on Waiting For Godot. It is an astounding play by Samuel Beckett; “a play in which nothing happens, twice”. The play’s landscape is barren, its universe is forsaken, an environment that eerily evokes the abandonment that pervades our cities under lockdown today. The lecture was hosted under an open sky, began at noon, and lasted till it became dark, quite dark. It was delivered by a professor who looked not unlike a god himself. He progressed from one page to another, reading dialogues, explaining words, playing the parts, pausing every now and then to check if we were keeping up. The lecture gathered a strange kind of sanctity as it proceeded. Everyone realised that it needed to press on uninterrupted, ironic as it may be, like a sermon. As I got drawn in I felt the ground on which we sat unguarded becoming thinner, gravity was giving up on us, abandoning its grip on our soles as if to become feeble and weightless like the page we were on.

The lecture lasted 7hrs, and left us with a strange fatigue, not unlike that of having run a marathon, only without sweat. In the play Godot never comes, but that evening godlessness did arrive at the end. I remember struggling for words, my mouth melting like flesh exposed to an incinerator, making lips indistinguishable, turning them inside, making it impossible to utter even a customary goodbye or thank you to the professor. I had grown up with a faint distrust of religion, but even so, I hadn’t expected that the final moment of evacuation, of becoming godless, would occur on a perfectly ordinary day sitting on humdrum grass, with not so much a word of warning, amidst a quiet modest middle spring. Journey back home that day felt longer than the lecture had lasted, perhaps because what I had eventually experienced was grief. An odd kind- grief without anchor, without an accompanying personal sentiment, adrift, but grief nonetheless. I woke up the following morning and latched onto my friend’s arm, who at the time was my roommate, and given to piety. I dragged him out in the open, and exclaimed, ‘God doesn’t exist. Oh my god, God doesn’t exist!’ My gasping squawky cries of relief baffled him. He said, ‘ok, ok.. ok hmmm’, and walked back indoors unimpressed. I wanted to express to him that I had had an intense and profound experience, that godlessness had left me feeling exalted, euphoric, devastated. I wanted to know if he feels equally overwhelmed when he experiences godliness. But he didn’t turn back. He wouldn’t hear any of it. And that was that.

As far back as 1772, Baron d'Holbach said that all children are born atheists; they have no idea of God. Is then the journey towards Godlessness through shedding, in some part, what was learnt in becoming adult? Is it a kind of forgetting? Once when an actor needed to prepare himself to play a character in Beckett’s play, he began by observing people suffering from dementia. Beckett’s characters keep ‘failing to remember’- where they are, how they got there. “Nothing to be done” is the opening line. Waiting For Godot is the perfect play to read 70 years after it was written, as we sit at home to save humanity by doing nothing. We have all become characters in Beckett’s godless universe.

If we go on to survive the pandemic (which we will), it will be owed in no small measure to the grit of a growing tribe of atheists who march on to deliver godlessness (in the form of a vaccine to fight covid-19 this time?). As the world moves forward, it will undoubtedly have more and more atheists. In his book ‘Letter to a Christian Nation’, Sam Harris wrote: “Atheism is a term that should not even exist… Atheism is nothing more than the noises reasonable people make in the presence of unjustified religious beliefs.”

In classic subcontinental style, we could look at the whole thing the other way around instead. It is God who experiences ‘humanlessness’; people have forsaken him/her because people are simply too busy living. Kiran Nagarkar best captures this in an anecdote in his book The Arsonist -

“If you had to choose between a woman you loved and God, who would you choose.”

The Weaver said, ”The woman.”

And the mullah asked him, “If you had to choose between a song and God, what would you pick?”

The Weaver said, “The song.”

And the priest asked him, “A beautiful sunset or God?”

The Weaver said, “The sunset.”

And they asked him how he could blaspheme so.

The Weaver said, “God has eternity on his side, he can always wait. Will the woman, the song, or the sunset wait for me?”

To be God is to be without people for eternity. To be human is to be without God for eternity. Either way, we are on our own.

Covid-19 App

“At some point during the lockdown, I cannot remember when, we were asked to download this app on our phones. You know, there was paranoia all around. This app was really simple, it was free, worked like they promised. When you stepped out, you’d get an alert if someone near you was infected. We’d call the police, they’d take them away. You can't blame anybody. Everybody was scared, you know. By the time the pandemic ended, this app was like a part of our lives. You still couldn't trust people, you know. It was the first thing you checked when you went to shop, or to the park, or took the bus. Check the app to see what kind of people you are surrounded by - not only those who were infected, but also other profiles - like if there were foreigners in your area, or smokers or meat eaters around you. A few moths later, the app could tell you even more- like if anybody sitting around you in a restaurant is gay, or if they'd been to jail. You never know what these people go to jail for. I set an alert for shops owned by the kufi-people.. you can never be too safe, you know. Then last month, we began receiving tasks, like wake up at 3:20am and watch the national parade. Or this task to go to the roof at 6:46pm, stand right on the edge, and salute. Post photos. It feels so great doing it, like we are all doing it together at that very moment, millions of us. Feels like I am a part of something bigger, you know. I receive badges for completing tasks, some users have a massive fan following. And now we get these alerts, like someone's profile gets tagged in red, someone whose score falls to the bottom, someone who isn’t completing tasks, isn’t participating like they should. Other users start making fun of them, abuse them, like really troll them and if enough people do it - this is the new feature - the app ‘exposes’ the traitors! It reveals everything about them - their house address, profession, phone number, everything! Have you downloaded the app yet? What happened, why do you look horrified?”

“These people you say who are getting ‘exposed’?”

“Yes”

“They killed one of them”

“What?”

“Yes, they killed him. His body was found outside his house. They dragged him out, they killed him.”

“Is it in the news?”

“No, its on the app. The video clips, so many of them. They have a new menu option for these videos now - 2mins Hate.”

“Oh.. I can’t believe it.”

“Yes”

“Have they sent a new task yet?”

((A scene from a play written & performed in 2022)

Humbly Roti

On a zoom conference yesterday, when I requested for meeting times to be kept for post lunch hours, I invited a spontaneous sneer. Pre-lunch time is for domestic chores and cooking, I explained. The jeering continued. All men. Which got me thinking - men do not expect to take household chores as a valid reason to be busy from other men. And what can be less ‘manly’ than making rotis. My father encouraged and cheered me on to participate in household work when I was young, and I’m grateful for it. I learnt to cook and clean fairly early, but it was not until I had a kid of my own that I began to make rotis. Here’s to rotis - that humble ubiquitous round piece of moon, ordinary yet so precious. Men: make rotis, feed the people you love, feed yourself.

Hold Me Comrade One More Time

I rewrote the song ‘hit me baby one more time’ by Britney Spears for what we are experiencing today. Spears recently made a call for strike and wealth redistribution amidst covid19 crisis. In india, 27 people have died because of exposure to the COVID 19 virus, but 22 migrant workers have already died while trying to escape homelessness and hunger caused by the inept 21 day lockdown. My government is killing me -

Oh baby, baby, how was I supposed to know

That something wasn't right with us?

Oh baby, baby, I shouldn't have let those revolutions go

And now I'm quarantined, yeah

Show me how the world should be

Tell me, baby, 'cause I need to know now, oh because

My government is killing me (and I)

I must confess I still believe (still believe)

When I'm locked inside I lose my mind

Give me a sign

Hold me, comrade, one more time

Oh baby, baby

The reason I breathe is healthcare

Boy, they got us blinded

Oh, so money-minded

There's nothing that I wouldn't do

It's not the way we planned it

Show me how the world should be

Tell me, baby, 'cause I need to know now, oh because

My government is killing me (and I)

I must confess I still believe (still believe)

When I'm locked inside I lose my mind

Give me a sign

Hold me, comrade, one more time.

Post-Pandemic Theatre

Today, World Theatre Day comes amidst a pandemic, and so we need to ask - what does this mean for theatre? Among the first venues to shut down globally were theatres, big and small. Among the first people to get affected by the city-wide lockdown were performing artists: all upcoming shows got cancelled immediately, rehearsals were called off, grants promised were put on hold. It is easy to shut theatre down because it is not listed under “essential services”, not for the ones whose lives do not depend on it. Social distancing has come as anathema to theatre which requires social intimacy as a necessary condition to come into existence. So far, only one country has announced financial assistance to arts institutions and independent artists who face uncertainty amid restrictions on large gatherings and events. “This situation can cause considerable distress. Artists are not only indispensable, but also vital, especially now…I will not let them down,” the minister of state for culture in Germany, Monika Grütters, said in a statement.

The thought of a minister expressing concern and doing all she can for artists-in-need is enough to bring me to tears. As an artist in India, the most I hope for, and I am not joking, is for the state to not interfere with my work, not censor my work. To allow me to show what I make. “Allow” - a dismally low bar of expectations from a state known to posses no inclination to work for artists. The budget for culture is a measly 0.2 percent of the total state expenditure, and grapevine has it that once during a cabinet reshuffle, the government forgot to assign a minister to the culture portfolio altogether. We in India are not alone in being marooned; performing artists in several nations are among the most vulnerable professionals. They live off shows and projects by the month; they complete one, get paid, move to the next one, and that’s how they keep the stream of money flowing. It is a thin stream, with not a drop more to allow uncertain survival to mistakenly, for a fleeting moment, turn into assurance and certitude in living. I frankly cannot fathom how artists muster up the courage and passion to endure this extreme precarity, but they do. And this I am grateful for.

But, what if this moment is not simply a call for increased state-support, but also a catalyst of change in theatre? Can we find ways to keep making theatre without being ‘in the theatre’? Do we always need to gather in each other’s proximity for theatre to occur? I am aware that these questions will bring a frown upon many a guru who insist, and rightly so, that theatre demands a community formed by social proximity, and needs people to gather somewhere. What if this somewhere is not one physical space but several? What if we summon a community that is physically distant but socially together, theatrically intimate? Experiments in this direction are already underway. The National Theatre (U.K.) is going to stream a free play every Thursday night from now on. The New York Metropolitan Opera will stream its shows for free every night too. Scholars have been interested in knowing how audiences experience live performance and their live-streaming counterparts, and have tried to understand how people, who increasingly inhabit an environment saturated with digital media, respond to contemporary theatre-streaming. Does theatre mean the same thing to an online audience as it does to an audience physically co-present in the same venue? Must it mean the same thing? Independent theatre practitioners have embraced the internet to conduct rehearsals, and also organise spontaneous “story-telling” sessions. I can mention dozens of work from the pre-pandemic past where artists have explored a blend of digital-physical ways to invent new theatrical forms, including a few works which I have developed with others. These experiments occupied the margins in their time, perhaps they can now reshape the contours of what theatre practice can mean in a post-pandemic world.

Theatre is no longer the kind of mass medium it was once imagined to be - take a look at the staggering number of people routinely gathering to watch live streaming, putting the attendance of any popular play to shame. IGTV, Facebook live, YouTube concerts, virtual parties, all are community formations ‘in the live', showing us that theatre is no longer the only place where people flock to ‘be together’. I have come to believe that we obstinately continue with theatre practices we inherited from the age of machines, from the analogue, approaches and techniques bound by peculiar relations of time, space, labour, value, and aesthetics. In the age of hybrid-medium, we need to think of theatres that are dispersed not concentrated, distributed not centralised, de-authored not copyrighted, collective not collecting. We are most likely entering a post-pandemic world with exponentially increased surveillance, stricter border control, confined human agency, and a new normal for freedoms we took for granted so far. How theatre responds to this new paradigm, what new ways of resisting and performing it invents, will decide how vital or dispensable it becomes in times to come.

On Gardens

Is garden a place or a thing? Gardens could be thought of as possessing consciousness, just the way forests do. Gardens are nature-artificial in the sense that they are designed, pruned, planted, planned, nurtured, protected, enclosed. Garden is what we imagine it to be beyond earth (think of what paradise essentially is, or call to mind any serene scene from mythic drama). Garden doesn't belong to earth, it is elsewhere that has been brought to earth. Hope shares the same enclosure. Hope must also be designed, planted, planned for, nurtured, protected, fenced. Hope too is a place, and a thing. Hope too is from somewhere beyond earth.

ITFoK Curation 2020 - IV

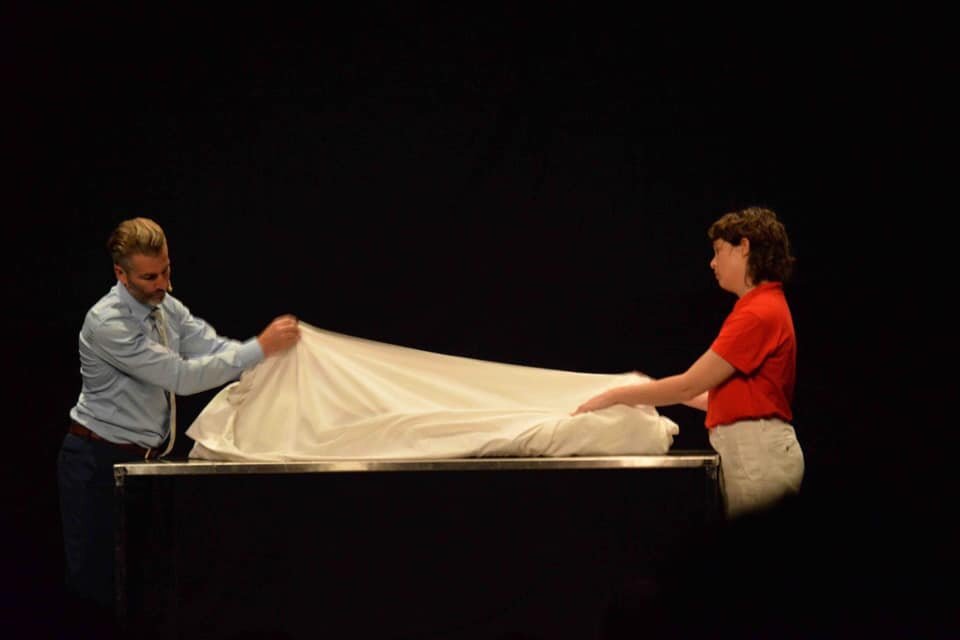

The Director (Australia) : A bold new performance by Aphids starring a real life funeral director Scott Turnbull, and theatre director Lara Thoms. Taking up a universal experience and taboo topic, they demystify, expose and expand elements of the death industry, using humour and first-hand knowledge to dig a little deeper on what happens after we go.

Tree Of Death (Poland): The show, presented by Pijana Sypialnia Theatre, derives inspiration from the Polish legend of the magical pear tree in which the Lady Death is imprisoned. Psalms are reworked to sing a critique of shallow customs of death, as performers enact surreal and absurd scenarios about a dystopic future in which death abandons mankind, leaving people to ‘munch on popcorn’.

‘Kala Dhabba’ (Bhopal): Based on a 1938 Hindi short story ‘Bhediye’, Avijit Solanki’s play imagines the horror of a mob and the violence it unleashes on a migrating family. Performed with thousands of bricks, a cart and a family that keeps shrinking, a camera silently documents and projects the darkness of savagery on stage.

ITFoK Curation 2020 - III

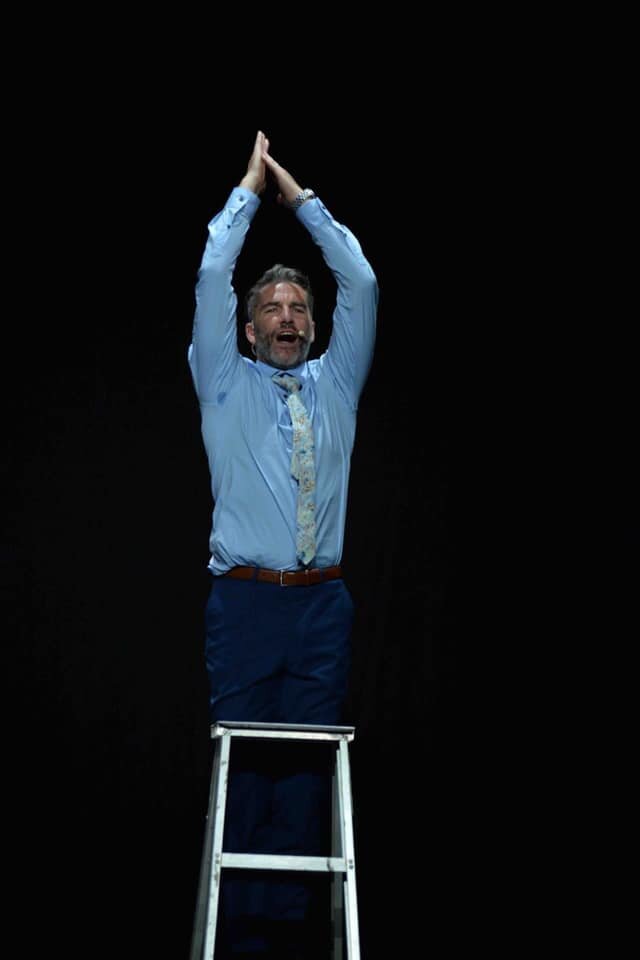

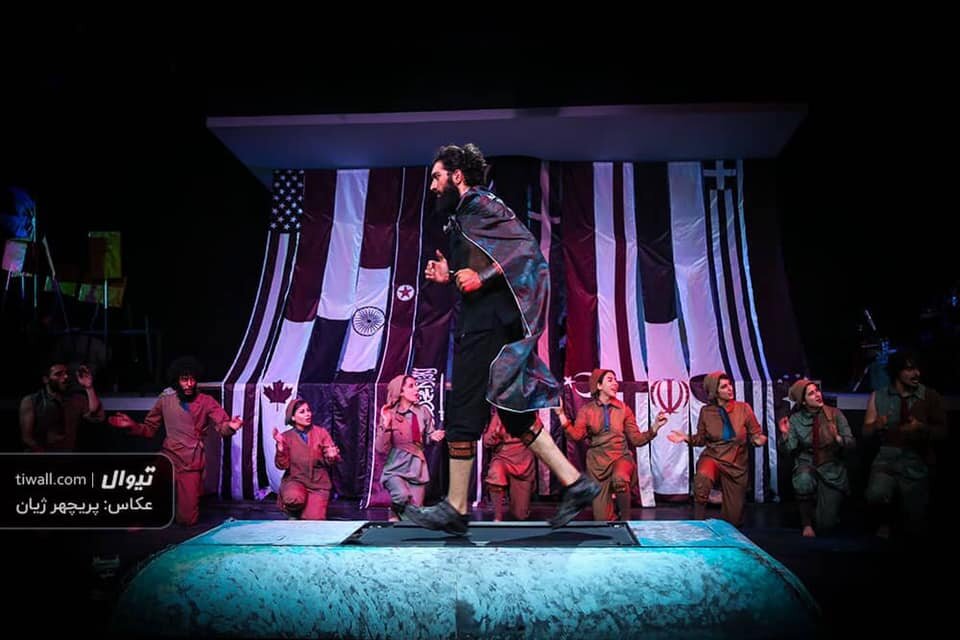

Coriolanus (Iran): When a despot is asked to show wounds from a war he falsely claims he fought for his people. When he is asked to prove why he deserves the trust of his people. When his people find out the truth and cast him out. The performing ensemble dedicated their show to the protesting and grieving people of Iran, and I, in my mind, to the courage of people on the streets in India today. Ali Rezania’s live music was mesmerizing, and Mostafa Koushk’s direction produced a spectacular act.

An Evening with an Immigrant (U.K.): An autobiographical account in a dozen or more poems, Inua Ellams tells his story of becoming a performer, having wine with the Queen and pursuing his quest for defining "home". Rarely have I heard a story of migration (from Nigeria to U.K. in this case) being told with such wit and self-reflexivity. I had first watched him perform at Edinburgh Fringe Festival in 2010/11, and took a secret vow to bring his work to India one day, and here he is.

The International Theatre Festival of Kerala hosted two exceptional plays yesterday, one minimal and intimate, the other clarion and spectacular.